Lost In Translation

The translation of climate loss into technical language, and the silence it creates in the process.

In conference rooms, they call it solastalgia—the pain of watching your home transform into something else.

A farmer’s failed crop.

A fisher’s empty net.

A herder’s bare pasture.

The first becomes a data point, the second a case study, the third a trend line.

This translation is necessary and expected.

To enter policy briefs, research papers, adaptation frameworks, loss must first be smoothened into something graphs can hold. The pain of seeing a way of life disappear must compress into quarterly reports.

This technical, academic language of climate change and mental health serves a purpose. It allows us to measure, plan, act, at scale. It creates common ground between policymakers, scientists, administrators. When they speak of vulnerability indices and stochastic modelling, they are reaching to grasp phenomena that defy our urban understanding.

But this language dominates more than it describes—it reshapes how we are allowed to speak of what is happening.

To be heard in the rooms where decisions are made, knowing when the birds arrive must become indigenous data indicators. A sacred grove dying is acute psychological distress. Community bonds – the sharing of boats, the lending of nets – are flattened when they become social resilience factors.

Traditional ways of knowing are dismantled and reassembled in a mould of expertise to be valid, heard, perhaps even funded.

Time also bends differently in frameworks than it does in places where the climate is already wrong. In conference rooms, climate change stretches forward in neat decades: 2050, 2080, 2100. The past exists as baseline data. The present is a point on a curve. But in the Sunderbans and Ladakh, time moves backwards too. Each changed season is measured against the memory of how it used to be, how something should have grown, how steady the streams once flowed.

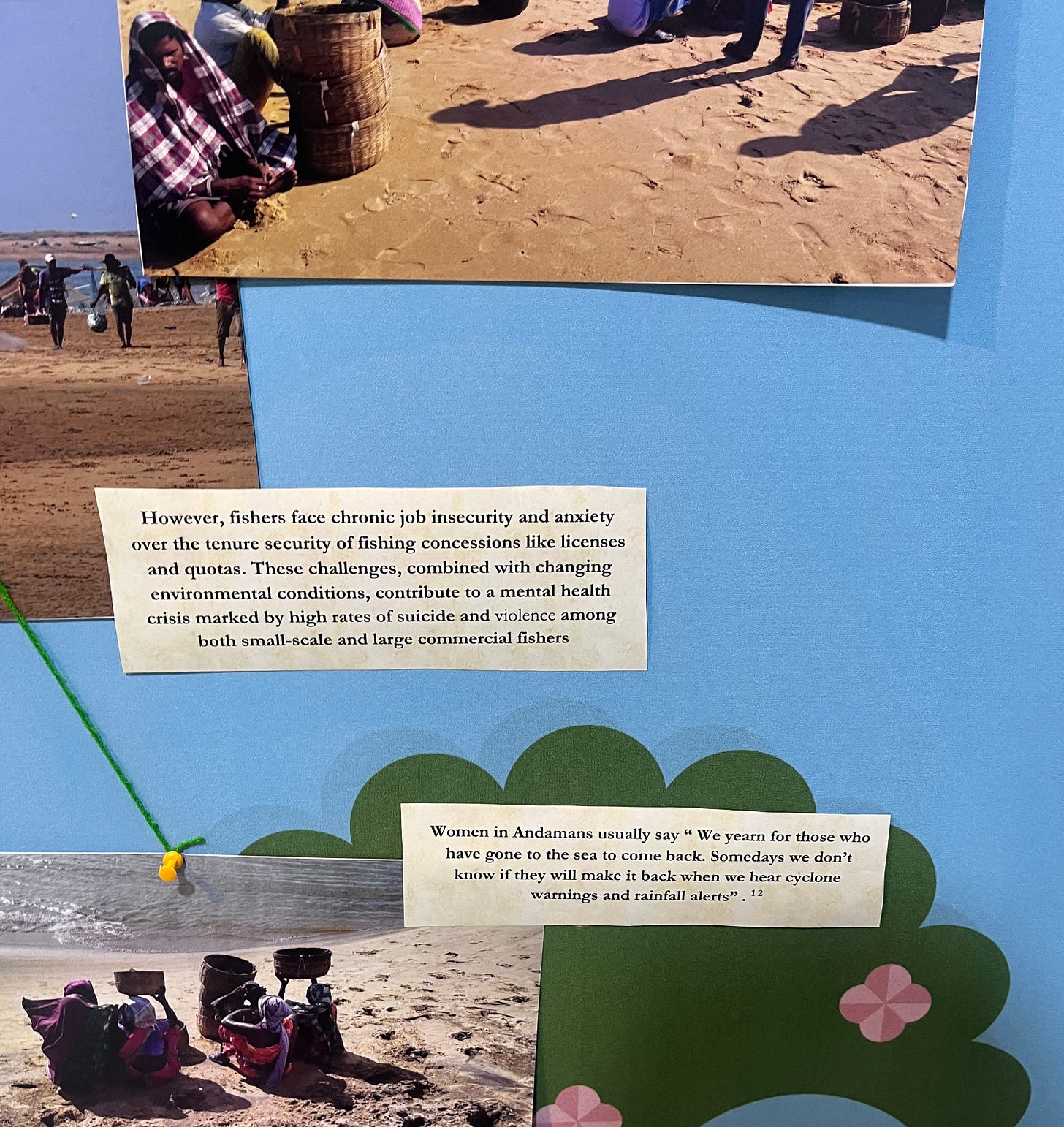

When asked how coastal communities articulate their experience of climate change, Dr Bhawna Rao, Senior Programme Associate at Dakshin Foundation – a non-profit committed to marine conservation and livelihoods in India – tells me no one there speaks of eco-anxiety. Instead, the men speak of empty nets, the ‘angry’ sea, of how the fish have moved further away, following colder waters. The women speak of empty plates, missed school fees and violent husbands with empty nets—and bottles.

Between these two languages lies a gap as wide as the warming seas.

But what if we could bridge this divide? Stories are the architecture of understanding, and the climate crisis presents us with a fundamental challenge around narrative and power. Whose stories get told? In whose language? What happens when we flip the hierarchy – when local knowledge leads and academic expertise follows? What would climate action look like if we let those closest to the crisis guide our response?

Across India, a few communities and organisations are already answering these questions, creating new grammars of climate knowledge.

In Tamil Nadu, Dakshin Foundation’s Coastal Grassroots Fellowship shows how visual knowledge can be reclaimed. Where government documents mark sterile zones and regulated areas, local women use GIS tools alongside hand-drawn maps and village walks to document living spaces – the mangroves, temples and community spaces absent from official records. Their visual language combines technical mapping with memories, bringing these spaces alive through family photographs, oral histories and public exhibitions.

In Maharashtra, Project Dharitri, an initiative by Asar and Baimanus, demonstrates the power of narrative knowledge. Women from climate-affected regions across ten districts report in Marathi for local and national media. Their journalism travels from Village Square to BBC Marathi, from Mongabay India to Loksatta, each story preserved in the language of those who live it.

In Pune’s Bhor block, Prayas Health Group has shown how participatory knowledge can transform understanding of climate change. Through thirty dialogues across nine villages, they engaged 374 residents using hand-drawn picture stories, diagrams made with local symbols, and village timelines stretching back three decades. Through this climate science found its way into the vernacular and the hierarchy of knowledge, inverted, however slightly.

To flip this dynamic consistently and earnestly requires more than good intentions.

Research institutions and universities could cede space and authority. This might mean relocating to the communities they study, building long-term local monitoring systems, and moving away from the parachute model of dropping in with pre-determined surveys. Picture community-run field stations where local experts shape core questions and work as equals with scientists and researchers.

Funding organisations could evolve their metrics of success. What if priority went to projects where traditional knowledge holders design and lead research? How about communities retaining ownership of research tools—from water testing kits to mapping software—after studies end, allowing them to continue monitoring their environments? Or projects growing organically instead of researchers arriving with pre-set theses. A village’s concern about changing fish patterns might lead to joint studies of water quality, which might reveal new questions about mangrove health.

Perhaps most fundamentally, expertise itself could transform. Imagine climate science taught through both statistical models and oral histories. Consider policy documents written first in local languages, then translated to technical terms. Think of impact measured not just in publications and citations, but in stories of resilience: a grandmother’s seeds that still sprout, a village that still stands, a sea that still gives.

This is not mere translation. It is transformation – of how we speak about climate change, how we understand it, and ultimately, how we might face it together.

This article is the first in a three-part storytelling collaboration supported by Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies, extending the conversations around mental health and its various intersections explored at Mannotsava 2024.

Oh what a brilliant piece, I can see SOFTBOIL becoming one of my north stars when it comes to sanely and intelligently navigating the worlds of fundraising, business and philanthropy. Keep em' coming! Cheers!

Such a refreshing take on the role of citizenry is solving systemic and complex issues. Thank you for doing what you do!